The opportunity canvas

The TLDR version (11 minute read)

This is post is about right-sizing your governance ‘document’ in agile investment portfolios depending on your level of uncertainty of scope or appetite for de-risking early stage investments.

There was a reoccurring theme while working in my last role as a value delivery consultant. Business Cases are rarely helpful in the long term for investment decisions where there is uncertainty in the scope or the desired outcome to be delivered through investment.

This article compares a few different options for disposing with the traditional Business Case in favor of the most minimal possible format that helps you invest in a desired outcome (business performance) rather than an output (a thing, platform or product).

If you have seen or been involved with projects at your business that have lost sight of their goal and just keep burning through money even though the project team know what they are building will deliver a poor user experience or will be trash-canned or replaced in the near future, then this article is for you. If you don’t want to read about why or when you should use one and just want to get started with building your own opportunity canvas, click this link to the canvas resources page to download the template.

A burning platform for change

In 2018, Special Inquirer, John Langoulant AO presented a report slamming a number of government institutions for their approach to investment decisioning which was considered opaque and wasteful. I was fortunate enough to be part of the solution for one of the two affected Government Trading Entities, moving part of the projects portfolio to an approach that would be more responsive to change and learning along the way for project teams while maintaining a level of traceability and accountability. The ‘Langoulant Report’ was the burning bridge that would drive change in my organisation at the time and I love a good burning bridge when it means there’s a problem to solve. I’m glad I can share some of the learning from that journey here.

“I am confident that the recommendations outlined in this document will better prepare the State Government for the challenges of a contemporary business environment, limit wasteful expenditure and offer an increased level of accountability to taxpayers”

What’s so bad about the Business Case?

So, we’ve heard about the traditional business case but what about a user story or a business model canvas? They are effectively artefacts or documents that intend to answer the same question: What should I spend my money and attention on? They attempt to create a standardised format to allow an ‘apples to apples’ comparison of investments.

So why shouldn’t I just use a business case? It describes an opportunity investment in terms of it’s intent, it’s scope and typically, a financial analysis of a one or more detailed options that if executed would give a deterministic outcome. Sometimes this is offered as a prediction of Return on Investment (ROI) or Net Present Value (NPV) being helpful indicators of financial returns at least. It is often written in a very ‘deterministic’ prose which implies certainty in terms of what will result from investment given a set of detailed assumptions that are rarely questioned.

Unfortunately, to get to this point and to this level of detail, a great deal of predictive analysis is required. In an environment where value is well defined and outcomes are highly predictable (say the routine replacement of large motor), the business case works well. As we learned in the Langoulant Report though, we are increasingly facing situations of disruption where that investment in up-front scoping of a deterministic solution is becoming less of a helpful approach. If it’s something we haven’t done or built before, we don’t have a good chance of predicting the outcome right from the beginning,

Spark New Zealand came to a point where they realised they needed to confront their faulty assumption that signed-off business plans would deliver what they projected after years of missed targets.

You might be thinking: So build a less onerous business case then! Shorten the template, reduce the requirements for detailed analysis then!

Been there. In the case of transformative agendas and new scope that hasn’t been tackled by the business before, you need a change in mindset that goes with the new nature of the work, not just a change in document template. In this case, we need to address the false hypothesis that investment in uncertain opportunities will deliver a deterministic (certain) outcome that is often characterised by the one-off release of funding or light-touch ‘steering committee’ that often get set up alongside a ‘signed-off’ business case.

No project portfolio has infinite money or infinite labour to execute value-adding work so at the end of the day, these documents intend to propose what a set of investors should expect to get back for an investment of X dollars or Y people. While many people have asked me about ‘what hoops they need to jump through’ to get budget to work on project Z, I tend to avoid the procedural answer of ‘fill in this document then present it to body A then get a signature from person B’ because that misses the point of the problem solving, prioritisation and risk mitigation process when managing a portfolio of opportunities. A pitch for funding should present the case for delivering the highest value for a given investment (we’ll get to ‘speed to value’ later) whatever a portfolio defines value as at multiple levels of investment maturity. While NPV and ROI are helpful indicators of long term financial returns, in a disrupted environment they falter which is where the world of start-up firms and new business models might have something to teach us.

What can established businesses learn from the start up world to augment more traditional portfolio management processes? Enter the Business Model Canvas and the investment mindset that goes with it.

If I were a start-up (or a venture capital firm)…

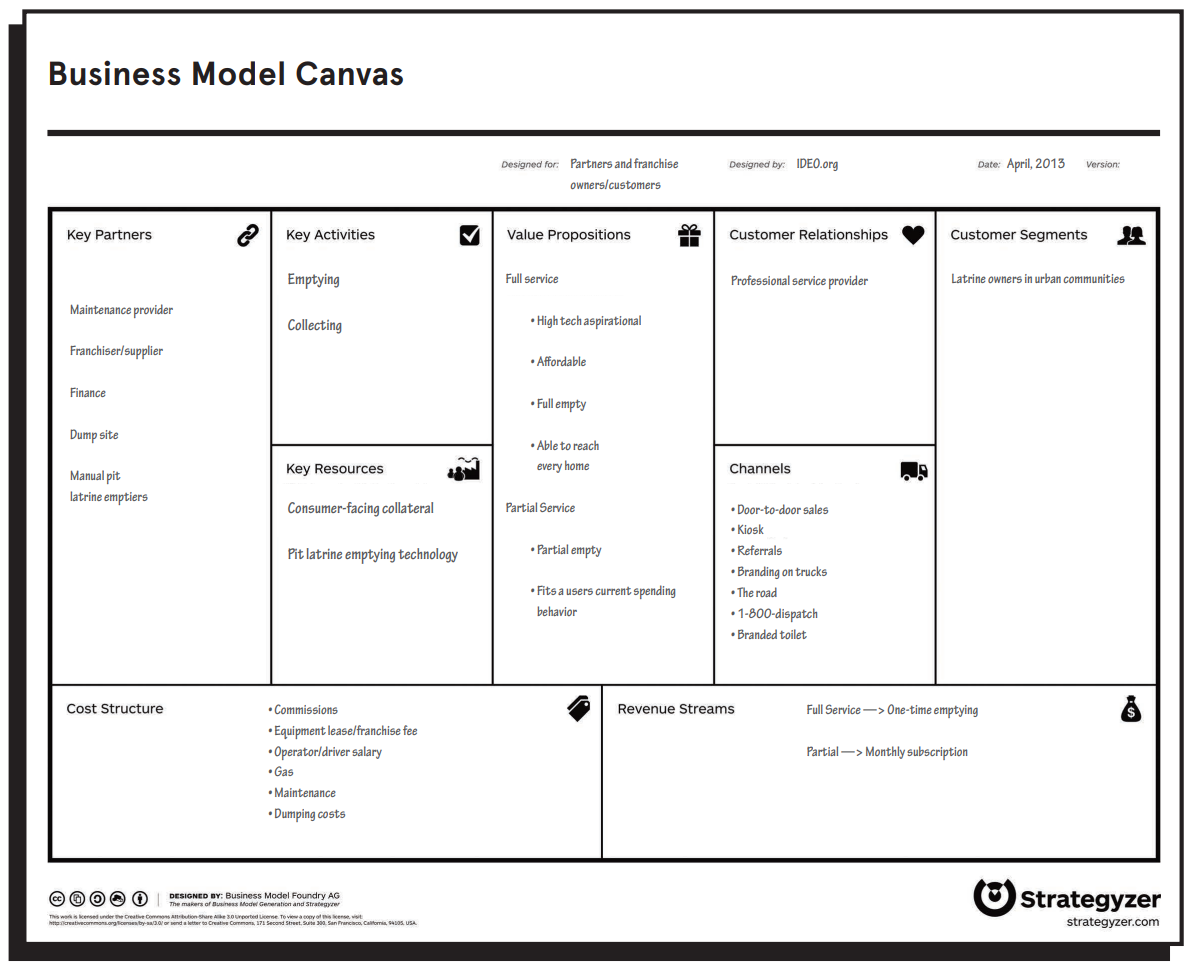

This canvas (by Strategyzer) is included in the handy ‘Field Guide to Human-Centred Design’ resource that IDEO.org share to enable anyone trying to solve a problem while balancing desirability, viability and feasibility.

If you can’t get a bank to invest in your new business idea, you might consider approaching ‘venture capitalists’ to give you a pot of money in exchange for a small slice of the ownership of your new business. While a typical pitch for investment in this ‘shark tank’ type environment will come in the form of a 10-20 slide deck or a punchy speech, more work goes on in the background to get to that point. If they’re fortunate, new founders will understand a design thinking approach to de-risking their idea and will often be introduced to the ‘Business Model Canvas’ to capture and summarise their new business idea in a 1-page format.

Alex Osterwalder of Strategyzer puts forward a great case in his landmark book ‘Business Model Generation’ (and this blog article) for how to derisk an investment in a new business model by asking 9 critical questions. This canvas serves as a platform for a coaching conversation with an A3 piece of paper to check you’ve covered most of the bases that new businesses will often fail at if not considered.

If you want to learn more about it, read the book or turn to Google to find many re-packagings of the canvas and Strategyzer’s advice.

Strategyzer sometimes sections it’s canvas to highlight key reasons an idea will fail if a part of the canvas is ignored (from Alex’s Blog).

In this context, the Business Model Canvas is an evolutionary step. It takes us away from a business case document that is typically deterministic and internally focused (what is the solution and how much will it cost) to one that considers the customer more actively. By examining the desirability, viability and feasibility of the idea, we get a more balanced view of an idea’s potential and we spell out some of the assumptions that need to be challenged if we’re to find out whether the proposed solution is likely to solve a typically ‘human centred’ problem.

Once again, it’s not so much about the template as it is the conversation that goes with it. In the venture capital space, the entrepreneur pitches based on a vision of what the product could look like in the future given a set of assumptions about the customer, the market size, the suitability of the envisioned product to solve a need and the financial viability of the product once at scale. It’s about securing just enough funding to consolidate a perpetually ‘work in progress’ vision of the future. The goal is not deterministic and if the assumptions don’t pan out the way the entrepreneur expected, the venture fund will have only invested in the money required to prove out the viability of the product, not to scale something that may never deliver on the final vision.

A PowerPoint template of the business model canvas is available for download here.

Why don’t we de-risk our assumptions and investments in companies with this sort of incremental funding approach? It turns out some businesses do use this approach to spur on internal innovation and change. Sometimes, one just has to create the right brand of venture capitalism that resonates with a company’s culture so it can make this transformative change.

One of the issues with the business model canvas that I’ve faced in the context of idea prioritisation within existing, project-driven organisations is that this document is, as the name suggests, more suited to new ‘business models’ rather than ‘projects’ or ‘opportunities’ within a corporate context that might not be focused on growing it’s portfolio of future business models (which is already fantastically described in Strategyzer’s ‘the invincible company’).

How might we bring elements of the business model canvas in to a project investment decisioning framework where building new business models is not a strategic focus for the projects portfolio?

The canvas evolves to suit organisations

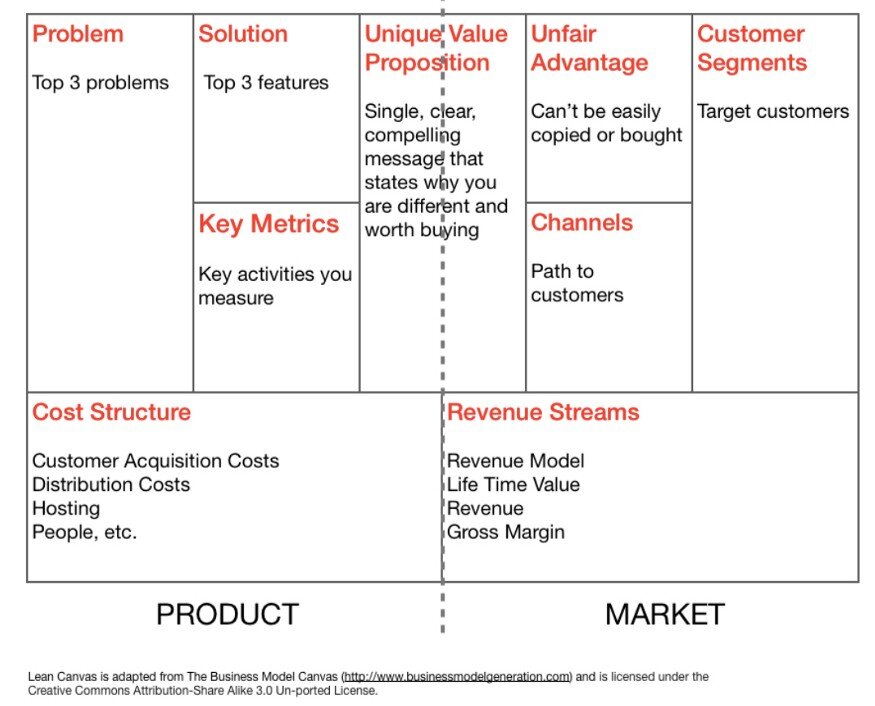

The Lean Canvas emerged shortly after the Business Model canvas (2010) as an incremental change. Inspired by Eric Ries ‘The Lean Startup’, the lean canvas was tweaked for entrepreneurs by Ash Maurya. In 2014, Jeff Patton would release his definitive book on User Story Mapping and a couple of years after that, he shared a rather brief post introducing the Opportunity Canvas shown below.

Since then, the opportunity canvas has gone all over the place.

I first ran in to it as a way to succinctly capture the details of opportunities in a digital portfolio. It helped me ask each of these 9 cell-bound questions at ever deeper levels as initiatives matured and entered more risky stages of investment. I got to walk through this template with Product Owners, team stakeholders and leaders charged with deciding on where best to invest the company’s resources. It was most useful in the context of prioritisation forums where forum decision makers needed a way to compare investments and make calls on whether to invest in opportunity A or B. They needed a ‘one-pager’ that could serve as the accessible ‘table of contents’ for other potential reference material about the opportunity.

The canvas evolves to suit a particular organisation

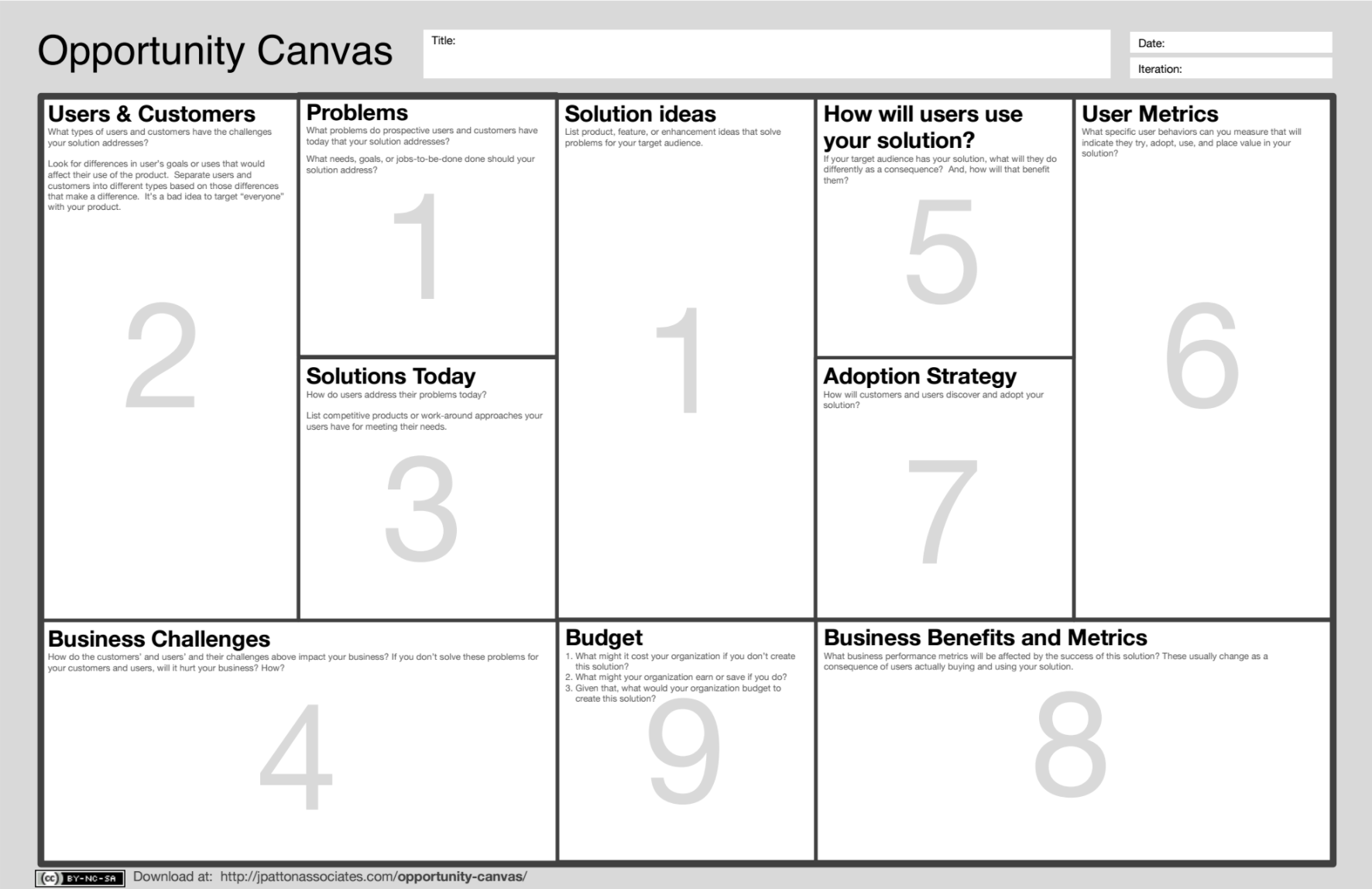

There is no one ‘off the shelf’ design of an opportunity canvas that will be the right fit for your organisation and culture. There are good starting points that may have evolved to suit the context and learnings of particular organisations. Here are two instances of opportunity canvases:

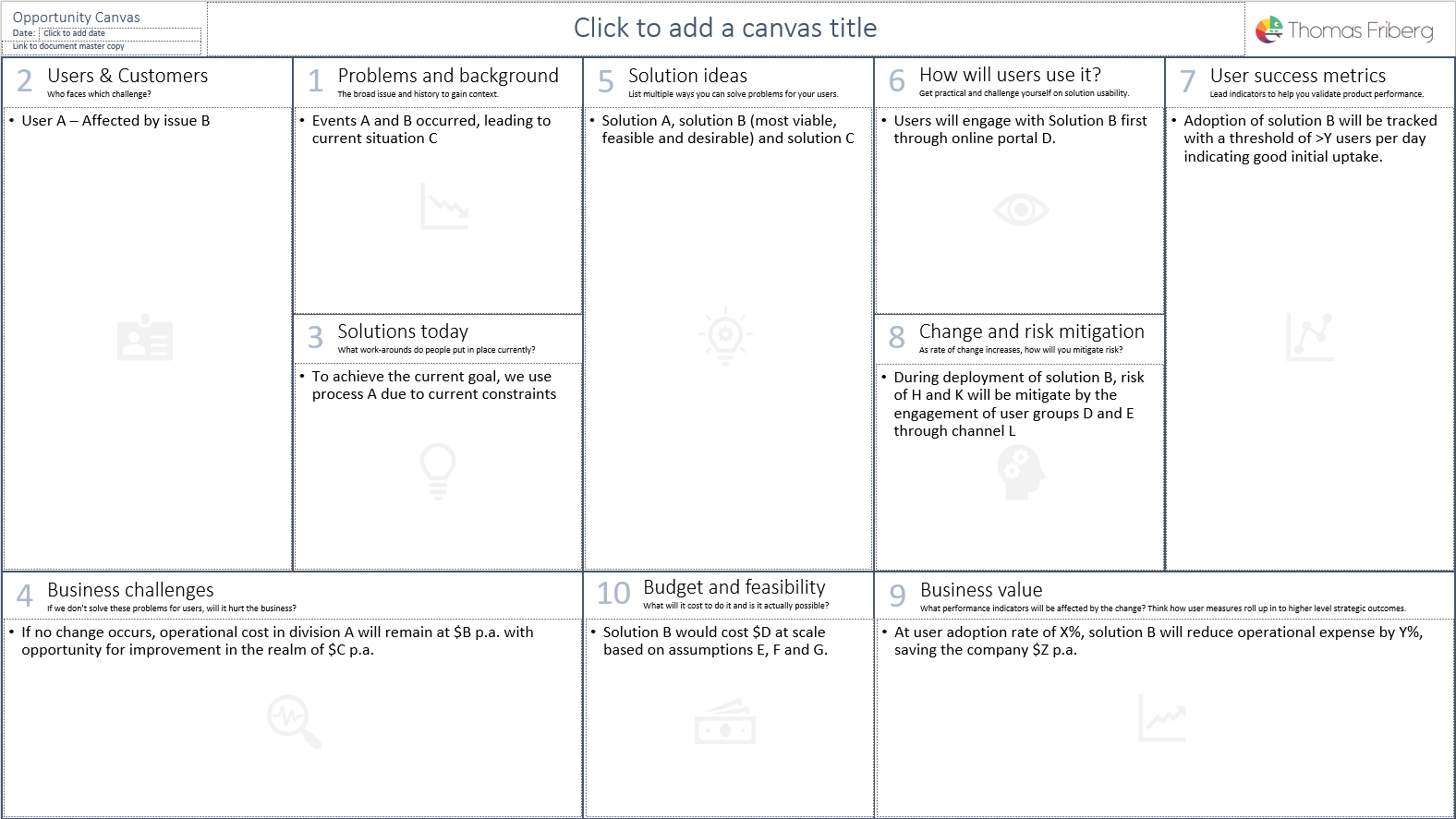

A PowerPoint template of my simple take on the opportunity canvas is available for download here.

The canvas follows a similar design convention to the Strategyzer canvas in terms layout but moves from left to right, checking for Desirability, then Feasibility and Viability.

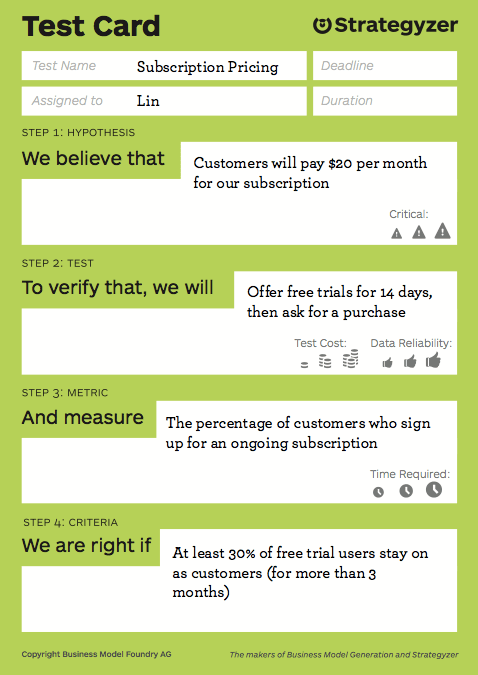

My take on the canvas largely stems from it’s use to facilitate the conversation with product owners as they define what their proposed product is and as they ask themselves what will need to be true for their products to be desirable, feasible and viable. It is intended to be light-weight with only 2-4 bullet points per box. It is a pitching aid and is geared primarily towards early stage ideas. That being said, I’ve seen this canvas grow to a more validated form as an opportunity has gone to a more mature state of delivery too (at a scale-up decision point) where it’s proved as a handy summary and a one-page ‘table of contents’ for more detailed learning from previous investment rounds. In Strategyzer parlance, there may be hypothesis/test and learning cards that sit behind validated assumptions that are stated on the canvas. It can still be used as a way to compare early and late stage opportunities in a single portfolio prioritisation forum.

The benefit of this template is that it’s quite good for skeptical new-comers. For those who are getting started with an iterative form of scope definition and investment and want to try out and alternative to a long-winded business case. It is refreshing for those stakeholders to think that a 1-pager could replace a business case to get to the first iteration investment decision. It can help them understand that the canvas can be a ‘living document’ that is as rough as the assumptions on the page to start with. It has been a useful template to print out and sit with Product Owners or idea generators to ask a minimum number of helpful questions to kick the tyres of an idea so that we might do some early filtering and prioritisation of possible opportunities. Where it is less capable is when people try to cram in too much detail which is why it is designed with finite space - it has an intent to distil for the purpose of pitching and sharing.

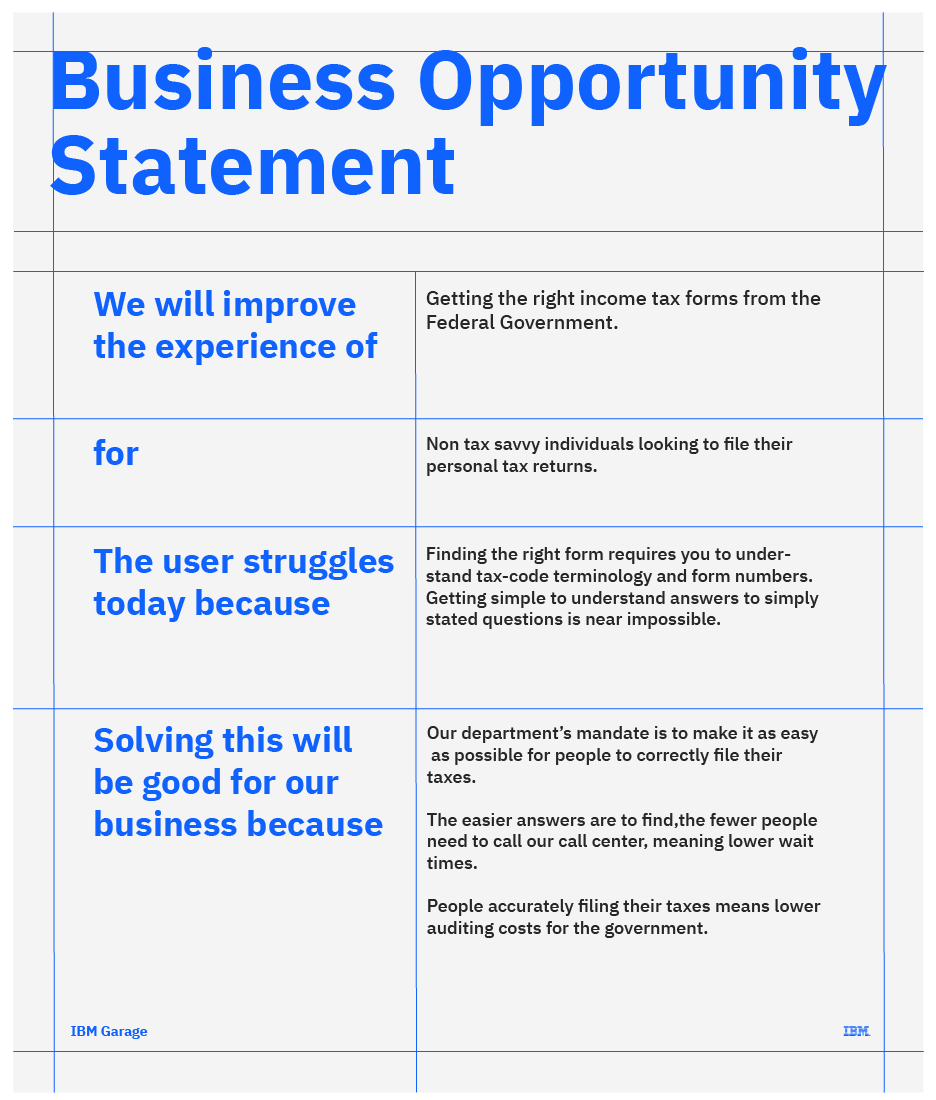

For portfolios that seek more rigor in the feasibility or ‘the how’ space, or that want more space to capture insights about the development of later stage opportunities, this two-page example is from IBM Garage:

IBM makes this canvas available on MURAL via this page on Enterprise Design Thinking.

Many of the cells on the first page are similar to my canvas above. Where the differences are relate to the second page which connects the canvas with the specific form of portfolio governance adopted by IBM Garage. The second page is rarely used for early stage opportunities but as the opportunity comes back to a funding forum (the 'Garage board’), it can help a Product Owner collect their product history in terms of challenges faced and where dependencies need to be called out in a systematic way to ensure a portfolio runs smoothly at scale. More questions imply that IBM has learned from things that have been missed in previous iterations of the canvas and that it can help clients de-risk their approach if they follow the Garage Playbook, at least in the early days as they learn how to work in a different way of working. In particular, the impediments and constraints process helps squads to run at ‘startup speed within the enterprise’ which helps them to deliver ‘speed to value’, a highly prized goal of an IBM Garage. For more information about IBM Garage, have a look at this post by my colleague, Dr. Mohamed El-Refai.

In the context of the Garage, this canvas combines with a 12 week investment cycle to force a renewal of questioning around the canvas. What did we learn from the last 12 weeks and do we want to keep investing? This is one of the key differences between the environment where business cases are used vs opportunity canvases.

Getting simpler and faster

If the IBM Garage canvas is more prescriptive than most, some thought leaders have also gone the other way as a way to reduce overhead once they work within a mature environment where most people are already accustomed to asking the 9 to 16 questions featured in the canvas. In these places where investors and Product Owners are all thinking the same thing regarding criteria for desirability, feasibility and viability, they reduce the cycle time on investment. Where a business case may entail a 6 to 24 month term of investment, a canvas may imply a 2-6 month investment cycle. For lighter weight canvases, feature cards or user stories, the investment cycle may be managed by a Product Owner autonomously at the resolution of 1-4 weeks! As we trust (and incentivise) Product Owners to deliver business outcomes (rather than deliverables/outputs) as efficiently as possible given guardrails of a problem statement or a time-boxed funding envelope, they will begin to oppose any overhead or documentation that obstructs their ability to enable their squad to deliver value. So, here are some examples of documents that organisations use to communicate the intent of their investments at the light-weight side:

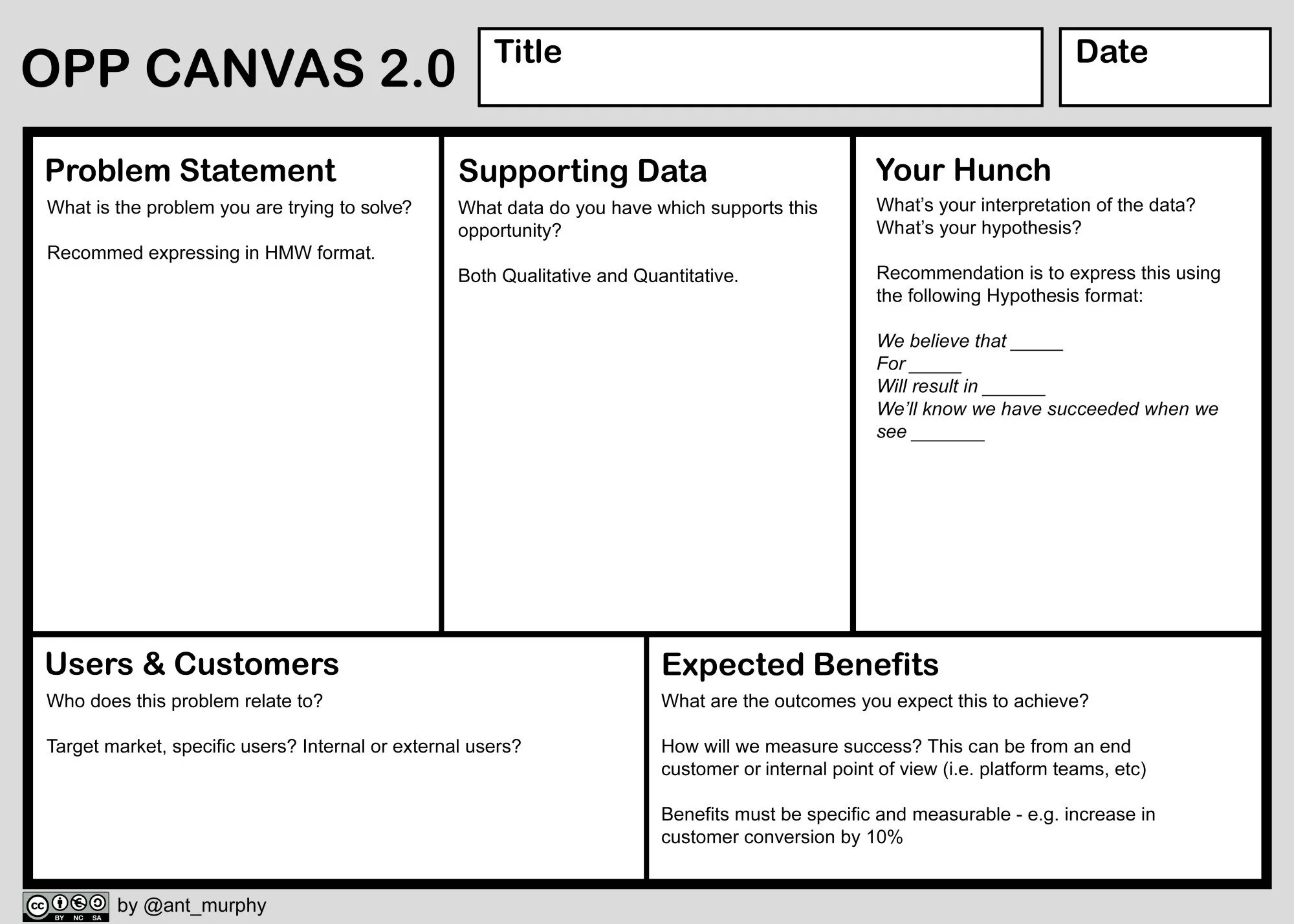

Ant Murphy of productprofessionals.com shared this paired-back version of the canvas in 2020. In practice, it merges 10 cells down to 5 by just allowing more flexibility in how the questions are answered. Good for groups of Product Owners who are looking for an incremental simplification to a long-running portfolio that has previously leveraged larger canvases.

For teams that use SCRUM to breakdown, prioritise and deliver their products, they will be familiar with this common user story template. A Product Owner may choose to pitch a collection of these user stories as a product increment or Feature that is tightly integrated with marginal overhead to the delivery team. This may be considered the most utopian situation where there is very little portfolio governance and these cards are considered as acceptable traceability for investment.

Pick the one to suit your organisation’s appetite

I hope you see now that there is a wide spectrum of documents and templates that might be better than a traditional business case for your organisation to use when it comes to expressing the value of an investment. The key is not about the document but the way of working that it enables. These templates all expect that the investment decision will be revisited as teams learn and that the document will be iterated on or quickly be replaced by the next hypothesis or feature, based on those new learnings. They are resilient to uncertainty because they anticipate change and plan it in to an investment cycle and prioritisation framework.

Of course, just changing a document template is not enough to get a different outcome from a portfolio of opportunities that requires prioritisation. It takes a change in mindset among practitioners and leaders. That’s where it’s important to engage experienced advisors to look for the signs that a chosen template and portfolio management framework is not working well in the context of your organisation so you can tweak it early and often. The templates are to facilitate change in people and their way of thinking which is where that experience really helps.

Try out my opportunity canvas template, following the helper text and let me know how you go! Is it the right fit for your organisation? How have your experiences been with previous business cases? Has your organisation increased the frequency of how they assess the performance of ‘signed-off’ investments?

Fortunately, I get to experiment and learn in this space every day in my role as a Value Orchestrator at IBM. I focus mostly on the ‘Viability’ aspects of the canvas but know how it all connects to make an attractive investment. The opportunity canvas is a tool to enable prioritisation and at scale, with many possible investments, it becomes necessary to back up the canvas with a solid line of opportunity to value to a strategic outcome. I look forward to sharing more about my learnings in the portfolio prioritisation space in the new year!